Not long ago, a much valued friend was reading through an article on karpophoreo.com. After finishing, but before talking about the actual content of the article, she had a couple of questions. The first was, “I know that ‘exegesis’ refers to interpretation, so why not just use the word ‘interpretation’?” The second question was, “what is ‘hermeneutics’?” Later, someone else asked me what ‘eisegesis’ means.

My friends had raised some very good questions.

I thought about maybe removing these terms from the website, but then decided instead to keep using them, but include occasional reminders of what they mean.

So why not remove them altogether as many people are not familiar with these terms? Well, if I had a desire to learn about a totally different subject area, one in which I currently lack knowledge, it is inevitable I would come across unfamiliar terminology. This is because all spheres of knowledge have their own distinct vocabulary.

There was a time we did not know every word we now know

If I wanted to learn how to become a good cook, I would inevitably come across terms such as ‘coddle’, ‘parboil’, and ‘baste’. Each term conveys something about cooking, and someone serious about cooking will learn to recognise what that is. I would not expect recipe books to stop using these ‘alien’ terms simply because I was unfamiliar with them.

It is worth noting that all the thousands of words we have each learned during our lifetimes were at some point unfamiliar to us, and at times seemed totally alien to us. Yet we learned them all, and don’t think twice about using them now, whenever they are needed. So why should the field of knowledge that is concerned with interpretation be any different…?

I don’t think it should be.

If we are serious about studying the scriptures, we will want to learn how to interpret them well. This entails not only learning what to do, but also what not to do. It involves learning to distinguish between good practice and bad practice, good ways of thinking and bad ways of thinking. It means developing an awareness of how it is we come to a place of understanding. This is where our terms – exegesis, eisegesis, and hermeneutics – take centre stage, and in so doing actually help us.

Exegesis

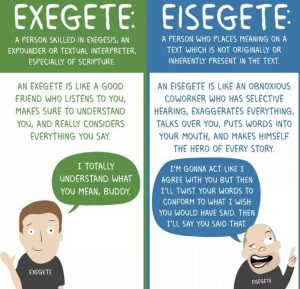

Exegesis means to draw out of the text the meaning that is already there. It is the attempt to determine the original meaning of the text. What did it mean in its original context? How did the first hearers or readers understand it?

Exegesis is essential for good interpretation.

Someone who practises exegesis is called an exegete.

Exegesis is great! Simply put, we need as much exegesis as we can get.

If exegesis was all we needed to concern ourselves with, then that would be wonderful. However, we must be aware of the other side of the coin, that is if we don’t want to potentially ruin our interpretation. The other side of the coin is something called eisegesis.

Eisegesis

Eisegesis is when we read into the text ideas and concepts that are absent from the original intent, context and meaning of the text. This then contaminates our interpretation.

Eisegesis is bad. It is a mishandling of the text and leads to erroneous interpretation.

Someone who practises eisegesis is called an eisegete.

Unfortunately, what is not generally realised is that there is a sense in which we all indulge in eisegesis. When we approach a passage, we always do so with what are called presuppositions. Our presuppositions come from our world-view, the assumptions we make about everything, including the texts we interpret.

Eisegesis often happens when we just unthinkingly assume that we know what the text means. We unconsciously read our own ideas into the text, when in reality those ideas are not actually there. It is very easy to allow our biases and presuppositions to be read into the text, resulting in an erroneous interpretation.

Interestingly, the very same thing can be said concerning relationships. If we eisegete our relationships – for example by assuming an erroneous motivation for someone’s actions – then we will interpret the situation wrongly. We shall look at relational eisegesis at another time though. Today let’s stick to the interpretation of texts.

As an example of unconscious eisegesis we could take the attribute of God’s sovereignty. The head of any State has sovereignty over its subjects or citizens. This means that the Sovereign has power and authority over the lives of the people. However, several hundred years after the New Testament was written, certain theological traditions introduced their own theological meaning into the definition of sovereignty, and unfortunately that meaning goes well beyond the normal definition of the word. Instead of taking sovereignty to mean power and authority, they read ‘actively exercising meticulous control over all things’ into the word.

The problem is, this is not the definition of sovereignty, and it certainly was not understood in that way by the various writers of the Bible. The theologically loaded definition of ‘actively exercising meticulous control over all things’ was read into the word ‘sovereignty’ hundreds of years after the original authors wrote the New Testament. In other words, the word ‘sovereignty’ has been eisegeted.

Power and authority can include some element of control, but it is ‘begging the question’ (a logical fallacy) to assume that power and authority must include the meticulous control over all things. When you stop to think about it, a god who can only exercise power and authority to achieve its ends by meticulously controlling all things is a pretty insipid and weak ‘god’. The God who does not need to meticulously control all things, yet can still achieve his purposes, is infinitely more powerful and impressive. The former is not the God of the Bible; the latter is. For the Christian, it is super-important to think rightly about God. If we add alien philosophical concepts into what God has revealed about Himself, then we are guilty of constructing an image of something that is not actually the true God.

It is at this point that someone determined (no pun intended!) to hold on to an erroneous definition of sovereignty will attempt one last throw of the dice. Psalm 115:3 clearly says, ‘our God is in heaven, he does whatever pleases him‘. And this is true. The problem is, you can’t assume that what pleases God is to meticulously control all things! Once again, they have come full circle and returned to the fallacy of begging the question so as to support their eisegesis (reading something into the text). As if to prove the point, Psalm 115 itself goes on to say in verse 16, ‘the highest heavens belong to the Lord, but the earth he has given to mankind’. In His sovereignty, God has delegated an element of control and dominion to His image-bearers on earth.

Eisegetical chain-reaction of error

Once a loaded concept is read into various biblical passages (i.e., eisegesis), erroneous results will inevitably follow. In our example, the initial eisegesis of assuming an alien meaning of the word ‘sovereignty’ gives rise to a chain reaction of further eisegesis that contaminates any further interpretation. It spreads like leaven, unseen and undetected, compounding the error as it progresses through the the text and through our reasoning.

Initially, maybe a single word is affected, but the infection then spreads out to a sentence or two. Before we know it, whole concepts and ideas have unknowingly been altered from the original intended meaning of the text. Ultimately, the natural progression of such eisegesis can lead to aberrant theologies that subtly lead people astray from the pure truth of God’s Word. All this takes place under the guise of ‘biblical interpretation’.

In this particular example of sovereignty, the desire to impose the philosophical concept of pre-determinism from outside the Bible, into the biblical text, has resulted in an eisegetical chain-reaction of error that simply was not there in the meaning of the original text.

On guard

To guard against such eisegesis, we must be aware of our presuppositions, our pre-understandings, our assumptions.

This involves making sure we don’t just unquestioningly adopt definitions and ideas given in theological books written by biased authors, definitions and ideas that carry erroneous loaded meanings. We must first diligently test all things before we even start our interpretation of the text. That way we will hopefully practise good exegesis, and not unwanted eisegesis.

A good warning sign of possible eisegesis is when we find ourselves trying to explain texts away because they don’t seem to sit well with our theology. We might hear ourselves say something like, “well I know it seems to say that, but it must mean xxxxxx instead”. We try to squeeze the text into line with our theology. This should be a warning sign, a red flag if you like, that eisegesis has sneaked somewhere into our interpretation.

Remember, all of us without exception, have presuppositions. They are the lenses through which we perceive the text and the world around us. They form the pre-understanding upon which we build our interpretation. We are all, therefore, prone to eisegesis. In fact, it is debatable whether we can ever be 100% free of eisegesis. But this does not excuse us from striving to be good interpreters.

Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics is the science and art of interpretation. Someone who practises hermeneutics is called a hermeneut.

Hermeneutics starts with good exegesis.

Once we know, through our exegesis, what a text meant to its original audience, the next step is to cross what we could call the hermeneutical divide.

Our context in the 21st century is very different from that of the 1st century (or earlier). This is where hermeneutics comes in. We need to accurately translate the original meaning across the great chasm of time, geography, politics, culture, etc., so it has meaning for us today. How should we interpret the results of our exegesis so we can accurately apply it to our lives today?

Interestingly, the field of hermeneutics is not only concerned with the objective interpretation of the text, but also with how we subjectively come to understand and be transformed by the meaning revealed within that text.

I still don’t know what parboil, baste and coddle mean…

If I’m honest, I don’t really have any desire to learn in any depth the skills of cookery. I’ve tried it and found it to be very stressful for me. It does not interest me. As a result, I still don’t know what parboil, baste and coddle mean…

Interpretation, on the other hand, is a totally different matter. I want to learn to be a good interpreter, and am very aware that I have got a long way to go.

The apostle Paul wrote the following verse in a letter to his friend Timothy, ‘Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who does not need to be ashamed and who correctly handles the word of truth.’ (2 Timothy 2:15).

He was encouraging Timothy to do what all Christians should be aiming to do – correctly handle the word of truth. That was Paul’s way of saying, ‘correctly interpret the scriptures’.

We’ve looked at just three words – exegesis, eisegesis, and hermeneutics. The more we use them, the more we will become familiar with them. The more we use them, the more we will understand their meanings, even if we may need some reminders along the way. Remember, this was the case with every one of the thousands of words we have all learned throughout our lives. Why should these three words be any different?